Why Are Pandas Endangered?

For several decades, humans have put in a great deal of conservation efforts to increase the giant panda population. With that in mind, why are pandas endangered? What caused giant panda populations to fall, and what is being done to save pandas for future generations?

China’s Wild Panda Numbers Are Up

In 2016, the bamboo-eating giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) native to southern central China was reclassified as “vulnerable” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), after spending nearly 30 years on the “endangered species” list.

There are now an estimated 1,864 giant pandas on the planet, including a wild population beyond the geographic range where researchers have come to expect to find them.

And although this is terrific news, two new pieces of research show risk still exists for giant pandas in the wild due to infrastructure development and livestock grazing leading to habitat loss.

Panda Life and Biology

To understand why wild pandas have been threatened for so long, we must also understand their unique dietary and habitat needs.

Panda bears eat only bamboo, and consequently can only thrive in bamboo forest and mixed forests with high concentrations of the food source. These areas have been under threat by human activity throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

In ancient times, wild populations of giant pandas were known to extend to much of southern China, down to Vietnam and Myanmar, but large-scale climate change at the end of the ice age and deforestation by humans caused major habitat loss.

Today, pandas live in the Sichuan, Shaanxi, and Gansu provinces of China.

As large animals, giant pandas have very few natural predators but may be vulnerable to attacks from other animals like bears, snow leopards, and feral dogs. Historically, humans have hunted pandas for their fur, but thanks to their threatened species status, killing or maiming pandas — or trading in their pelts — may be punishable by the Chinese government.

Because the bamboo pandas eat has low nutritional density, they must consume a large amount of it every single day. As a result, pandas take a long time to digest their food and don’t live a very active lifestyle.

Pandas’ Mating Habits

Another factor in the dwindling giant panda population is that they often don’t produce enough cubs to sustain themselves. Female pandas are typically only fertile for a few days of the year, which means they may go multiple years between pregnancies.

The females may give birth to one or two cubs at a time, but only have the energy to take care of one. In the wild, the second cub is often left abandoned.

Panda Habitat Loss and Restoration

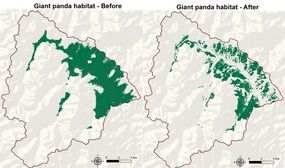

Both private and government entities continue to put in resources in order to help protect pandas, maintaining and restoring the population of wild pandas throughout China. A study published in the Sept. 25, 2017, issue of the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution looks at what brought about this population growth, and whether it’s likely to continue.

“What my colleagues and I wanted to know was how the panda’s habitat has changed over the last four decades, because the extent and connectivity of a species’ habitat is also a major factor in determining its risk of extinction,” said coauthor Stuart Pimm, professor of conservation ecology at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment, in a press release.

The researchers used satellite imagery data to figure out the change in land use over the panda’s entire geographic range. They found that between 1976 and 2001, bamboo forests decreased by 23 percent — but that it actually increased slightly between 2001 and 2013.

This encouraging trend has been due mostly to bans on commercial logging by humans in panda breeding grounds, as well as the establishment of dozens of panda reserves across China, and education for people living within these preserves.

But the changes in these panda-friendly areas of China haven’t all been good: Loads of new infrastructure like roads and hydropower stations has been built since 2001. “These have been the major factor in fragmenting the habitat,” said Pimm. “There was nearly three times the density of roads in 2013 than in 1976.”

Although there’s no single permanent solution to securing the conservation of these iconic animals, the research team suggests establishing panda corridors between the existing patches of habitat. That would allow the remaining wild pandas to find each other and prevent any part of the population from becoming isolated.

Bamboo Forests Dwindling

A separate cooperative research initiative conducted by Chinese and U.S. scientists looked at the impact of livestock on bamboo forests.

The second study, published online Oct. 3, 2017, in the journal Biological Conservation, found that over 15 years, livestock numbers in China’s Wanglang National Nature Preserve increased 900 percent, damaging one third of all giant panda habitat in the park.

“These problems are not unique to our study area, but common throughout the panda nature reserves and habitats. It is not just an ecological problem, but also a gamble between the communities, the nature reserves, local governments and other stakeholders,” added Li Sheng, an assistant professor of conservation biology at Peking University, China involved in the second study.

“This long-term monitoring shows that the pandas are being driven out of the areas that are heavily used by the livestock, especially the park’s valleys,” said Pimm, who participated in research for both studies. “These lower elevation areas are crucial for giant pandas, especially during winter and spring.”

Panda Captive Breeding Efforts

In addition to dedicating swathes of land as panda reserves, the Chinese government has also put resources into breeding pandas in zoos. Today, all captive pandas across the world are considered on loan from China, and any cubs born in captivity must be returned to their home country to further conservation efforts.

Breeding giant pandas is difficult because the animals only tend to mate every two or three years. Some experts have turned to artificial insemination of female pandas as a means to sustaining the captive population.

Originally published here